The Origin and Explanation of the “Threefold Vision”: Theology and Practice “for the sake of the Gospel”

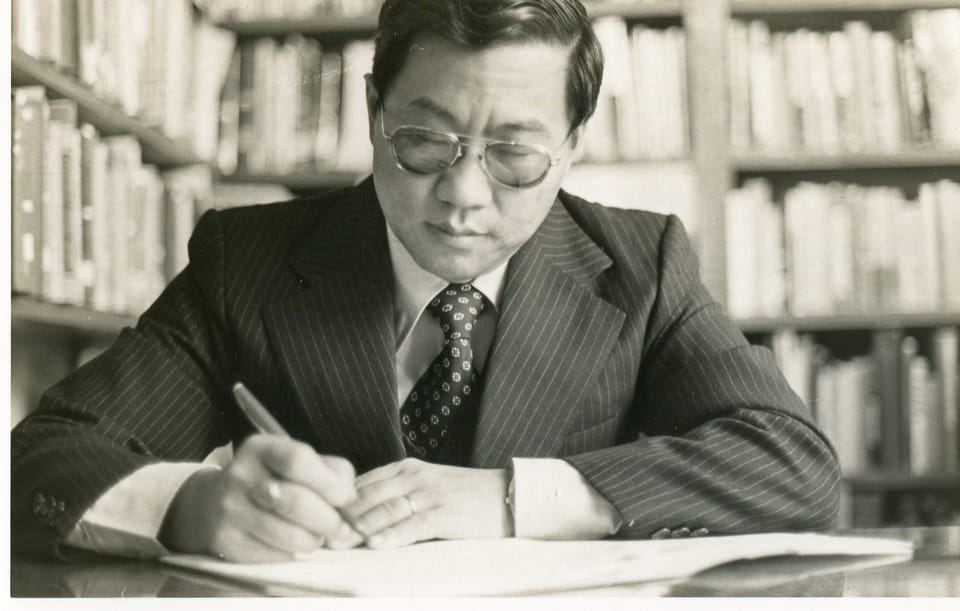

Ying Shan[1]

Jonathan Chao’s “Threefold Vision” was first fully presented at Taiwan’s Youth Mission Conference in July 1985.[2] Chao continued to share the vision through different channels after that. In 1990, as shown in the manuscripts from Taiwan CMI (China Ministries International) Coworker Conference and Christ’s College strategic planning meeting, Jonathan Chao gave the following explanation for the “Threefold Vision”:[3]

“Evangelization of China” — preach the Gospel to Chinese people, of which 95% are non-believers, including those in Mainland China.

“Kingdomization of Church”— take God’s redemptive historical work as the overall context and principle for missions, it mainly address to the issue of “egotism” easily found in churches and Christian organizations and the ignorance of God’s redemptive plan in history.

“Christianization of Culture”— transform Chinese culture with Christian values and faith, exerting Christian influence and taking leadership in the cultural, academic, educational, political and social spheres.

Jonathan Chao’s vision cannot be separated from his personal ministry experience. In fact, the origin of the “Threefold Vision” is closely related to his personal calling. We will first examine the background of the “Threefold Vision”, and then analyze the three points respectively.

I. Background

When elaborating on the historical development of the “Threefold Vision”, Chao emphasized his seven callings.[4] Chao was converted at the age of 14 and dedicated his whole life to preaching the Gospel at 15. His enthusiasm for preaching had never diminished since then, and his love and pursuit of the truth increase day by day. During his second year study of MDiv in the seminary, Chao received the unwavering call to return to the Far East and preach the Gospel to the Chinese people. This was partially due to “the influence of patriotism", but he also felt the Chinese people’s need for the Gospel.[5] Chao summarized three facets of his calling: 1) Love of the truth; 2) Influence of patriotism; and 3) Enthusiasm for leading people to the Lord. These background factors contributed to Chao’s vision and subsequent action, while his actions and experiences, in turn, made his vision and calling even more clear. Through extensive research on Chinese history and culture, and direct involvement in China missions, Chao’s commitment to Chinese ministries grew deeper over time.

For Chao, personal calling necessitated action and response. Through the interaction between calling and action, vision would become clearer. A notable example is when he received the call as a lifetime preacher – Chao then responded by attending to the seminary immediately after graduating from his undergraduate study. Similarly, in response to the call to evangelize the Chinese people, he chose to take a break from his seminary study and went to Taiwan, where he worked as a bible teacher on one hand, and got familiar with Chinese churches and seminaries on the other hand. Through these actions, Chao was convinced that education would be a powerful way to evangelize the Chinese people.[6] He believed that university education may help college students to grasp the essence and value of Christian beliefs and they may then influence the society after graduation. Theological education goes further by training mature Christian thinkers and educators who may establish Christian universities. Later, theological education became a pivotal aspect of Chao’s ministry. Chao not only expected graduates to shepherd the church, serving small numbers of believers, but he also desired to raise more and more Kingdom workers who will enthusiastically preach the Gospel to those who have never heard the good news. Moreover, he envisioned that the lives of these Kingdom workers would be transformed by Christian faith, and their life testimonies would finally transform the value systems of the entire society. From Chao’s goals of theological education, we can clearly see his vision of “Evangelization,” “Kingdomization,” and “Christianization”.

Chao often responded to callings with actions; he was a man of action. He knew that clarity of vision emerges through proactive actions. However, this did not mean that he would ignore theory, academic research was also a crucial component in living out the vision. He said: “Gospel work involves not only practical implementation, but also theoretical engagement, battling and defending theological and missionary thoughts.”[7] The emphasis of Chao’s vision was “for the sake of the Gospel.” However, in order for the Gospel to be truly understood by the Chinese people, it is essential to understand the situation in China, including important research topics such as China’s religious policies, the Three-Self churches and house churches in China, Chinese culture and Christianity, etc. He had established various China research centers successively,[8] providing a window for the global community to gain a deeper understanding about the Chinese church. Furthermore, Chao’s research on Chinese culture, political conditions, and churches significantly bolstered spiritual support for churches in China.[9] His research on Chinese culture and society also had a profound impact on the implementation of the vision of “Christianization of Culture.”

II. Evangelization of China[10]

1. Vision Development

The vision of “Evangelization of China” is undeniably derived from Chao’s personal enthusiasm for evangelism. When he received his call to ministry, he said to himself, “God showed me that the most meaningful and valuable investment in life is evangelism”.[11] This insight was the vision of “the spirit, heart, and faith”. As he answered the calling willingly and persistently, the vision became increasingly clear. God had also imparted the same shared vision to other brothers and sisters.[12] In addition to his zeal for evangelism, Chao’s Chinese identity also contributed to the development of the vision. In his essay “The Challenge of a Billion Souls,” Chao stated that the discussions about the mission strategies in China was founded among the western missionaries since 1843, the year following the “Opening of five treaty ports”, nevertheless, once China was opened in the 1980s, “Evangelization of China” should become an unavoidable topic for the Chinese church. Facing the reality of one billion unsaved souls in China, Chinese Christians have unshakable responsibility! [13]

In addition to Chao’s personal convictions, the situation of the Chinese society and churches in the 1980’s also demonstrated the necessity to “Evangelize China”. In the fifties, many Chinese youth actively participated in the construction of New China, but subsequent political movements wiped out the enthusiasm of these Chinese intellects. The tragic experience of the Cultural Revolution caused irreparable wounds to that generation. For decades two generations of young people experienced a crisis of faith and spiritual emptiness. The traditional Confucianism, Western science and liberal thought, and even Marxism-Leninism-Maoism (which was once seen as the hope for society), have all failed to provide a meaningful way of life. Chinese youth desire Western ideas on human rights and law-based society, but they neglect the fact that these ideas are rooted in Christianity. Therefore, for Chao, only evangelization and Christianization could provide a pathway for contemporary Chinese to restore the lost national dignity, to solve poverty problem in China, and to reintegrate a fragmented society.[14] Above all, in the 1980’s, through his analysis of historical development, Chao believed that God was opening the doors for the Gospel in China. He believed that with the change and opening of the economic system, the political restrictions in China would also slowly be relaxed. He had optimistically hoped that in this wave of openness, the Gospel work of house churches could also become a legitimate “normal religious activity”. Given these expanding opportunities, Chao called for churches at home and abroad to be prepared to “harvest” for the Lord.[15] Besides, Chao also pointed out that, despite the political pressure experienced by the Mainland churches, the number of Christians has not decreased; and God has continued to bless the house churches in Mainland China, leading people to find new hope for China in the Gospel! Chao believed that a group of itinerant preachers and house church leaders, who were willing to sacrifice themselves for the sake of the Gospel, would inspire more believers both at home and abroad to become more actively involved in the evangelization of China. In addition, the lack of resources in the Mainland church has also prompted people abroad to share various resources with them to support evangelical work.[16]

For Jonathan Chao, evangelizing China is to evangelize all Chinese people, not only those in the Mainland China. In the 1980’s, according to Chao’s estimates, there were 1.5 billion Chinese people in the world, but ninety-five percent of them had not yet heard the Gospel![17] Chao described the Chinese society as a pre-Christianized society,[18] and Chinese Christianity was still in the pre-Christian era.[19] To enter the later stage of evangelization and turn the Chinese society into a Christianized society, we must first spread the Gospel. When more Chinese people become Christians, they will live out the Christian values in society, which would gradually lead to the Christianization of the whole society. The historical development is such: first with quantitative development (evangelization of China), then through qualitative development of the church (Kingdomization of Church), and finally the influence of the Gospel being extended to the whole society (Christianization of Culture).[20] From this point of view, evangelization is the main premise of Kingdomization and Christianization. Without Evangelization, it is difficult to Kingdomize the church and to Christianize the culture.

2. The Implementation of the Vision

From 1983 to 2001, Chao frequently traveled to Mainland China to visit, investigate, and conduct research. He also actively engaged in training church workers to undertake the mission of evangelism.[21]

As to the implementation of “Evangelize China”, particularly for overseas audiences, he raised several key points, which in fact constituted the primary focus of the Center for Chinese Church Studies in the 1980’s. First of all, we should pray for the evangelization of China, pray for the leaders of China, and pray for believers in the Mainland China. Prayers will motivate people to know more about China’s politics, economy, and society. Second, we need to provide various spiritual resources for believers in the Mainland churches, such as Bibles and Christian publications, and provide pastoral care and training through virtual theological classes by radio broadcasting. Third, we call on Christians to contribute to the modernization of the Mainland China through investment or teaching science and technology courses.[22]

Another action to implement “Evangelization of China” is theological education. The theological education that Chao referred to is not only training pastors to provide pastoral care to the believers in the church, but also preparing them for missions. Students themselves need to be passionate about evangelism. Theological training should entail the study of Biblical truths so that students may deepen their understanding of redemption in Christ and apply it to their preaching. Theological training should also entail spiritual discipline, so that students can grow in spiritual maturity and strength as they live out the vision of evangelism.[23] Likewise, students need to have a good understanding of Chinese culture to facilitate their preaching among the Chinese people. This idea of mission-oriented theological education is also the institutional goal of the Chinese Mission Seminary in Hong Kong and Tao-sheng Theological Seminary in Taiwan. This type of training in theological education also has a direct impact on the Mainland church and on the evangelization of China. Later, the Chinese Church Research Center also shifted its focus from research and teaching to training.[24] The Training Manual for Church Workers is a training program for evangelists and pastors in China, which included courses like “The Bible and Salvation”, “Hermeneutics”, “Basic Theology”, etc. It was hoped that the training program would help to equip workers, spread the Gospel, strengthen the church, and make the life of believers more fully Christianized.[25]

3. The Meaning of the Vision

When asked about the essence of “evangelization”, Jonathan Chao clearly explained: “Evangelization refers to the process in which a region or a people receive the opportunity to hear the Gospel and to know Christ.”[26] He also pointed out that evangelization is a long process which cannot be completed in one era, but requires the efforts of generations for more and more Chinese people to be reached. Furthermore, evangelization is not just about “preaching” but more importantly is about how the Gospel influence the society, culture, and government constitution principles. This process is a movement that should not stop until the Lord returns.

For Jonathan Chao, the evangelization of China encompassed more than a mere campaign to spread the Gospel; it also held significant implications for missions and theological education. Evangelization calls for a shift in people’s attitudes toward Mainland China — no longer ignoring her, but seeing her as the beloved of the Lord. As we change our attitude, we would also get a renewed understanding about missions. In the past, mission work often referred to cross-cultural missions, ignoring the evangelization within culture. Chinese missions used to be dominated by the western churches, but now we need to develop a new approach of mission from the perspective of Chinese people. In terms of theological education, in the past, theological education was also dominated by the Western models and mostly focused on training urban middle-class pastors. Evangelization, however, has reawakened the need to train more evangelists, that is, to educate students not just to pastor the five percent of China’s population who are believers, but to reach the ninety-five percent who have not yet heard the Gospel. As people recognize the importance of evangelization, their attitudes towards Chinese culture and society would also change — faith should no longer be confined to the narrow circle of the church, but should be viewed as an integral core of the society and a mainstream in China’s historical development. Chao believed that God’s Kingdom surpassed all human powers, and that Christ’s redemption will enter the Chinese history under God’s sovereignty! Evangelization brings quantitative development, and when the local church acts according to God’s will, it will also bring about qualitative development. This allows God’s Kingdom to be manifest on earth, which is the vision of “Kingdomization of Church”.

III. Kingdomization of Church

1. Vision Development

In Jonathan Chao’s writings, the discussion of the “Threefold Vision” is mostly focused on “Evangelization of China" and “Christianization of Culture”. There is relatively little discussion about the “Kingdomization of Church”. As a matter of fact, the concept of “Kingdomization of Church” appeared at a later stage. Before the Youth Mission Conference in July 1985, when Jonathan Chao talked about his vision, he only mentioned “Evangelization of China” and “Christianization of church”. “In order to ‘Evangelize China’ and ‘Christianize the church’, we need to work together to develop God’s ministry.” [27]

Obviously, in Chao’s mind, “Evangelization” and “Christianization” were the first two facets of his vision. “Evangelization” refers to the transition from not knowing the Gospel of Jesus to becoming a believer; “Christianization”, on the other hand, centers on taking the Christian values as the guiding principle and foundation of daily thought, behavior, and life. It encompasses the Christianization of individual believers, church communities, and the entire social culture.[28] In fact, even in his later writings on the “Threefold Vision”, Chao also mentioned “Evangelization” and "Christianization” more. When Chao talked about the seven callings that led to the development of his vision, the sixth calling was about “theological education for the evangelization of China.” When talking about the issues of “indigenization, faith, and culture” in his seventh calling, “Christianize the culture” was also a major focus of discussion.[29] So when did the idea of Kingdomization appear? In particular, when did the term evolve from “Christianize the church" to “Kingdomize the church”? This evolution was not explicitly explained in Chao’s writings. But we know that in July 1985, at the Youth Mission Conference, Chao officially introduced the vision of “Kingdomization of Church”, alongside the visions of “Evangelization of China” and “Christianization of Culture”. [30]

The idea of “Kingdomization” seems to be less easily understood than the other two visions. In his discussion about how to "Kingdomize the church”, Mak pointed out that many English translations did not seem to capture the essence of this concept. Even when Chao first proposed this new term, both Chinese and overseas co-workers did not fully grasp its meaning.[31] To comprehend Chao’s concept of “Kingdomization”, we should start with “Evangelize China” and "Christianize the church”. The doctrine of church is also critical to the understanding of “Kingdomization of Church”. As mentioned earlier, Christianization is a broader concept that can be applied to individual believers, churches, and even the entire societies and cultures. As a unique and chosen group in the society, the church should be Christ-led in its thoughts and actions. It serves as an important witness in the world, promoting the renewal of society and culture towards a Christ-centered Kingdom. Therefore, aside from Christianization, the church entails a unique mission to manifest God’s sovereignty and to expand God’s Kingdom in the world. Therefore, the church has an indispensable role in moving from "evangelization" to "Christianization”. When the church manifests the Kingdom of God on earth, it also propels the whole society to Christianization. In light of this, the church needs to be “Kingdomized”.

The church manifests God’s Kingdom on earth and participates in God’s ultimate plan of redemption. From his study of the New Testament,[32] Chao concludes that God’s redemptive will is “to complete redemptive work in Christ, so that people may repent, and return to Him”.[33] The church is to align its mission with God’s redemptive historical plan and to strive to participate in it. Therefore, in his articulation of the “Threefold Vision”, Chao viewed “Kingdomization of Church” as “Taking God’s overall redemptive work as the context and guideline of all ministries.” [34] Deeply influenced by the Reformed theology, Chao believed that all human beings need to be redeemed. After the Fall, human nature was corrupted, the relationship with God was also distorted and even the order of the entire universe was also destroyed.[35] But God prepared a plan of redemption that was “planned by the Father, carried out by the Son, and implemented in each of our lives by the Holy Spirit.” [36] God’s redemptive history started from the Fall of Adam and would not be fully completed until the second coming of Christ. Meanwhile the church receives a mission on earth and participates in this plan of redemption under the sovereignty of the Lord.[37]

Chao’s vision of “Kingdomization of Church” based on the ecclesiology that resists sectarianism. If the church embraces its role in God’s redemptive history, it would not limit its ministry to simply “building up a physical church”.[38] Chao deeply understood the challenge for the church in achieving unity. He pointed out that the churches in China need to have a common statement of faith, as a way to express unity in truth, so that the church will not be easily swayed by heresies. In the past, the Chinese church was divided by denominations under the influence of Western missionaries. Despite moving away from Western sectarianism, there are still many factions among churches, they had no contact with each other, and even accuse each other, contrary to the Bible’s teaching of unity. Therefore, Chao advocated that, in dealing with some theological controversies, especially those that are not explicitly addressed in the Bible, it is necessary to firstly find out the key issue, then as long as everyone has a consensus on this key issues, they may then maintain their own opinions, be tolerant to the other’s ideas, and preserve unity in the Lord.[39] In a nutshell, the emergence of the vision of “Kingdomization of Church” is intricately linked to the church situation in China, and obviously it should also be the concern for the universal church.

2. The Implementation of the Vision

As mentioned above, in Chao’s writings, comparatively there is not much discussion about “Kingdomize the church”, nor about how to implement “Kingdomization”. However, the implementation of Kingdomization is inseparable from the ministry of the church and the training of believers. Chao’s ministry in Mainland China primarily focused on training and research. He also founded a number of seminaries, which he considers essential for the implementation of the “Threefold Vision”. In September 1985, the Chinese Church Research Center in Hong Kong launched a disciple training program. The director pointed out that the mission of all disciples was to establish and manifest the Kingdom of God. If a church lacks the sense of Kingdom of heaven, it is akin to a body without a soul. At the same time, without a visible church, the Kingdom of heaven cannot be manifested in the world. Disciples are called to live on earth with the sense of the Kingdom of heaven, so that the church would become a community that magnifying the Kingdom of heaven.[40] In 1988, Chao accepted the invitation to serve as the president of Christ’s College. He viewed this decision as “pivotal for advancing the implementation of the ‘Threefold Vision’.”[41] At that time, he intended to establish an undergraduate program, a theology program, and a Chinese studies program in Christ’s College, with a goal of training the students to preach the Gospel, pastor a church, and engage in cultural work, all guided by the “Threefold Vision”.[42] Therefore, the establishment of seminaries, the training of disciples and ministers with the sense of the Kingdom of heaven, and the manifestation of the Kingdom of heaven on earth — all of these are the implementations of “Kingdomization of Church”.

3. The Meaning of the Vision

The essence of “Kingdomization of Church” is to impart a broader vision to the church. This involves moving beyond egocentrism and the needs of individual churches, and God’s redemptive history as the core and direction of all ministries. In fact, in carrying out His plan of redemption, God has raised up different groups of people with various gifts and talents to establish His Kingdom. Chao pointed out: “If the church clearly understands God’s will, it will not prioritize simply on the building of physical church, but will actively engage in God’s redemptive work in history. Churches’ understanding and actions in this matter are called Kingdomization. The church is to align its mission with God’s plan of redemptive history. ”[43] In fact, the vision to “Kingdomization of Church” is particularly crucial for today’s church. Churches should break down the walls between one another, not only focusing on their own needs, but on God’s redemptive history plan. Achieving this broad vision and mind is not easy. The development of church ministry is not solely about increasing the size of the congregation. Church resources are not meant for solely raising their own leaders. The church should involve themselves in the development of God’s redemptive history, as Chao described, “not to play in circles, not to be methodological, but to move towards the Lord’s second return”.[44]

In Hong Kong, there are some well-resourced denominational churches that are willing to use their abundant resources to sponsor theological students from other denominations. These sponsored theological students are not obligated to the sponsoring church. This may be a beautiful illustration of the “Kingdomization of Church”. Nevertheless, it must be noted that Chao’s Kingdomization is centered on God’s redemptive historical plan from the beginning to the end; hence, Kingdomization does not just refer to “resource sharing” or “generosity and open-mindedness”. If these actions do not involve the church in God’s redemptive plan, they could not be called “Kingdomization”.

Besides, “Kingdomization of Church” is oriented towards the Lord’s return, and the hope of His second coming is the driving force for the church to witness God’s sovereignty in the world. Both believers and churches will go through many trials in the journey of faith. Faith in God needs nurturing so that we are spiritually empowered to face the trials. “Kingdomization of Church” includes the “eschatological hope”. This hope is a vital foundation for believers and the church as we bear witness for Christ on earth, and is also a source of strength for believers to support one another on the heavenly journey. As Chao put it:

It is only when you see God’s plan of redemption in Jesus Christ that you can find your place and be motivated to serve. People may fall, weaken, and fail, but God will never fall. Jesus will never be weakened, and His plan of salvation will never fail. When we put our hope in Christ, we can see our responsibilities to help others when they are weak, and we can be comforted and strengthened by the Lord in our own weaknesses. We will not lose our faith in God’s salvation plan because of our weaknesses.[45]

Believers and the church must believe that under God’s absolute sovereignty, He has been guiding the church in His plan of redemptive history. The task of the church and disciples is to preach the Gospel, so that more people can hear it and have their lives renewed in Christ. Ultimately not only the church, but also the entire culture and society may be Christianized.

IV. Christianization of Culture

1. Vision Development

The vision of “Christianization of Culture” cannot be separated from the vision of “Evangelization of China”. According to Chao, the vision of “Evangelization of China” led him to actively participate in China missions. In 1978, he founded the Chinese Church Research Center as a base for the study of the churches in China. Subsequently, in order to train more Gospel workers for China, the idea of establishing Chinese Mission Seminary first emerged in 1984, he then started a discipleship training program in 1985, and Chinese Mission Seminary was then formally established in Hong Kong in 1987. In the meantime, Chao assisted the re-opening of Tao-Sheng Theological Seminary in Taiwan with the hope to nurture more Kingdom workers through theological education to do Gospel work in Mainland China. In carrying out these missions, Chao came to the deep conviction that Gospel work should not just be limited to the relationship between the individual and God, but should be implemented in all walks of life. This gave rise to his sense of mission to rebuild Chinese culture.[46]

Jonathan Chao’s doctoral dissertation focused on the Anti-Christian movement in China during the twenties of the 20 century and the church’s response during that period. He pointed out that the negative impact of the Anti-Christian movement had persisted until this day, and there are still someone insisting that religious belief should not be associated with social education. Chao clearly stated that this was even more of a hindrance to Christianity than external persecution.[47] Chao believed that Christianity should exert influence and make unique contributions in the society. In fact, since the twenties and thirties of last century till today, the relationship between faith and culture remains an important topic in theological research. In his teaching, Chao often discussed the topic of Christian faith and Chinese culture, a subject of interest for students and believers. There was a group of young believers and intellectuals in Taiwan who were deeply concerned about how to integrate their faith with the culture. This concern ignited Chao’s calling for Taiwan.[48] In the spring of 1986, Chao established the Christianity and Chinese Culture Research Center in Taiwan, which held several seminars during 1986-87. At that time, Chao envisioned that “Hong Kong would be a great base for the Gospel work to the Mainland, and Taiwan would be suitable for the development of cultural Christianization. In the future, Taiwanese Christians' contributions to the Mainland may be in the areas of cultural reconstruction and theological education.”[49]

The development of (the vision of) “Christianization of Culture” is obviously related to Chao’s research on the relationship between the Gospel and Chinese culture. While promoting theological education, Chao often pondered, “How can we develop Biblical theology within the context of Chinese ideology, (including Marxism-Leninism)? How can we establish effective theological education in the contexts of the Chinese church and Chinese society? ”[50] In 1968, he enrolled in the PhD program of Oriental Studies at the University of Pennsylvania.[51] The following year, he established the Christianity Research Center in Philadelphia, where he promoted the Biblical ideology and edited The Seminarians and The Christianization of Culture.[52] During his studies, he took a number of courses in Chinese philosophy, culture, and literature to enhance his understanding of Chinese culture. In 1970, he published a research article on Christianity and Chinese culture,[53] and subsequently researched the relationship between the Gospel and Chinese culture from a historical perspective (including Chinese history and the history of Chinese missions).[54] These studies have become an important foundation for the “Threefold Vision”. The vision and mission of “Christianization of Culture” aim to encourage Chinese believers to bring Christian values into culture, which Chao regards as integral to the work of the Gospel.[55] The mission is to “influence Chinese culture with Christian ideology, to redeem China, transform Chinese culture, and assume leadership in cultural circles, thereby making Christianity the ideological mainstream of Chinese culture.”[56] Especially in the current state of cultural emptiness, Christians should bring hope to China’s future and contribute to the transformation of Chinese culture.[57]

2. The Implementation of the Vision

The implementation of the “Evangelization of China” involves training and sending workers to carry out the evangelistic work across the country. The implementation of the “Kingdomization of Church” involves developing the church ministry, training pastors with a Kingdom mind, and engaging the church in God’s redemptive plan. The implementation of “Christianization of Culture” lies partly in the study of Christianity and Chinese culture. Since 1978, following the establishment of the Chinese Church Research Center at the China Graduate School of Theology, Chao dedicated himself to the research on Mainland China. In the first three years, he mainly focused on reporting the changes in politics, culture, and religion in China, without much in-depth analysis. Later, he established three major directions for the research center: (1) to analyze the dynamics of politics, thought, culture, education, and religion in China; (2) to report on the trends and development of churches (both public and house gatherings) in China; and (3) to conduct preliminary research and data collection on the history of Christianity in China.[58] He hoped that studying the Chinese church and society from a Chinese perspective, rather than from a foreign perspective with the interests of foreign churches, would contribute to the overall development of the Chinese church.[59]

Jonathan Chao proposed to study Chinese society and the Chinese church from a Chinese perspective. His attitude was never just for the sake of research, but for the purpose of mission. From the beginning to the end, China was always in his deep concern, and preaching to the Chinese was the most important thing for him! Through his research, he hoped that those who have not heard the Gospel may know Jesus, and that believers will continue to grow in their spiritual lives and integrate their faith and culture. Therefore, for Chao, research and mission are inseparable. In fact, the insistence of this research direction also cost Chao a considerable price. In 1980, two years after the Chinese Church Research Center was founded within China Graduate School of Theology, he had a disagreement with some colleagues on the direction of the Research Center. His colleagues believed that the Research center was set up to support teaching and therefore disagreed with Chao’s continued participation in the China missions. Chao firmly believed that theological education should be set up for missions, and there was no conflict between missions and research. Therefore, in order to adhere to the vision of Chinese missions, he decided to separate the Research center from the school and establish an independent institution combining research and mission.[60] The Research Center’s bold historical analysis of China’s religious policy also made the Center a target of public criticism. Chao was even publicly rebuked by the leader of China Christian Council’s.[61] For Chao, he just intended to understand and analyze the China churches in an objective manner, to assess how the political changes influencing the church, and to develop appropriate strategies for China missions. These all can be attributed to his commitment to “Christianization of Culture”.

The implementation of “Christianization of Culture” also requires Christian professionals to live out the Christian values in their daily lives. On the one hand, these Christian professionals can contribute to society with their expertise. On the other hand, they can interpret their expertise with Biblical principles, which in turn lead to the integration of faith and culture. When the China Graduate School of Theology was first established (Chao was one of the school founders), it targeted the college graduates and emphasized advanced Biblical and theological studies, with a hope to work for the integration of Christianity with Chinese culture.[62] Clearly, Chao hoped to train a group of Chinese professionals through theological education to undertake the mission to “Christianization of Culture”. Later, Chao assumed the position of President of Christ’s College, intending to make the College a base for implementing the “Threefold Vision”, and to train Christian professionals to engage in the great cause of cultural Christianization.[63]

3. The Meaning of the Vision

One of the fundamental aspects of “Christianization of Culture” is to acknowledge the necessity for cultural renewal. Deeply influenced by the Reformed theology, Chao firmly believed that believers have a cultural mandate in the world. When God created human beings in His own image, He also appointed them to subdue the world. However, after the Fall, fallen humanity no longer fulfilled the cultural mandate. Instead, man only thought about benefitting themselves. Therefore, culture needs renewal. Mankind must first receive life renewal in Christ and then begin the process of sanctification, being transformed daily by the Holy Spirit in their thoughts, behavior, and life. Life transformation will not only affect the individual, but also slowly change the family, church, and even the whole society. To successfully renew culture, it is essential to first understand the ideologies prevailing in contemporary Chinese society and the folk beliefs that shape people’s lives. At the same time, people need to understand their own situation, their personal life, society, and history through the lens of the Gospel.[64]

Believers from all walks of life play an important role in advancing cultural Christianization. Professionals can integrate their faith into various spheres such as culture, education, medicine, and social welfare, leveraging their positions to exert influence in their respective fields with Christian values. When they exemplify Christian values in their daily lives, even ordinary Christians contribute to the gradual renewal and transformation of culture. Every believer “incarnate” in society every day. Their lives serve as channels for evangelism, and their living examples are crucial to the implementation of cultural Christianization. As Chao put it:

An evangelist must live a Christ-like life, guided by faith, hope, and love as the principles of their life. They must develop Biblical character, wisdom, humility, sound judgment, and compassion. An evangelist must embody the virtues of truthfulness, goodness, and beauty from Western ideology, as well as the virtues of wisdom, benevolence, and courage found in Eastern ideology. The evangelist must rely on the grace of God in exercising their spiritual authority. In sum, in order to help shape the future of their people, an evangelist of the time must live a godly life that honors the Lord, have a broad worldview and historic responsibility, and identify with the people.[65]

V. The Overall Implementation of the “Threefold Vision”

In Jonathan Chao’s life, his spiritual journal was characterized by the cycle of vision, calling, and action. God first gave him a spiritual vision, which evolved into a calling in his heart. Then, as he proactively responded with action, his vision became clearer and his calling more specific, deepening his commitment.[66] Therefore, through continuous practice and actions, his “Threefold Vision” became increasingly clearer.

After proposing the “Threefold Vision” in 1985, Jonathan Chao sought different ways to implement the vision. In 1988, one major endeavor was his assuming the presidency of Christ’s College. When asked how to develop the future of Christ’s College to maximize its contribution to the Kingdom mission, Chao replied, “Evidently, we need to train evangelists to Evangelize China, pastoral workers to Kingdomize the church, and Christian professionals to participate in Christianizing the culture.” After numerous discussions, in addition to the undergraduate program, Chao intended to establish the Center for Christian China Studies and the Graduate School of Theology in Christ’s College to carry out his vision.[67] Several of the college’s newsletters[68] show that Chao consistently upheld Christian theological principles during his presidency. Based on the cultural mandate God gave to man in Creation, Chao focused on the three disciplines: humanities and social sciences, natural sciences and theology. At the same time, he hoped to train students with the philosophy of Christian liberal arts education, shaping their character according to Christian values. For students who were believers, he offered courses of spirituality to nurture their spiritual growth. In addition, he planned to instill a vision about evangelism and mission, and encourage students to devote to the mission work after graduation in order to promote the implementation of the visions. Unfortunately, Chao and the Board of Trustees of Christ’s College were unable to reach a consensus regarding the plan to establish the Graduate School of Theology. Meanwhile, Chao recognized the urgent need for the Gospel work in Mainland China. In pursuit of his vision, he officially resigned from the college presidency in July 1992.[69] Although the Vision was not implemented through Christ’s College, Chao’s ten-year blueprint for Christ’s College did reflect the holistic approach to implement the “Threefold Vision”.

Aftermath, Chao redirected his ministry towards China Ministries International (CMI). In 1993, during CMI’s Morning Prayer meeting in Taipei, he reviewed and clarified the “Threefold Vision”. He also proposed that the implementation of the vision involves research, training, and sending, which has since become the core focus of CMI.

Chao’s implementation of the vision began with the establishment of the Chinese Church Research Center, and his studies of Chinese society and Chinese church. Later, in response to the needs of the church in China, Chao initiated the training of church workers. Eventually, CMI evolved into a mission-sending agency with direct involvement in China missions.[70] While continuing its research on Chinese society and Chinese church, CMI has also launched a range of training ministries, including: 1) a systematic three-level training course for Mainland workers titled “Theology On-Air”, broadcasted by the Global Broadcasting Corporation; 2) the establishment of the Discipleship Training Center, in Chinese Mission Seminary, Tao-sheng Theological Seminary, etc.. The purpose of these training ministries is to train believers to preach the Gospel in Mainland China. All of the biblical, theological and spiritual training aims to equip believers with a solid foundation for evangelism. Therefore, the implementation of the “Threefold Vision” entails: (1) conducting research to ensure effective training; (2) providing training to prepare disciples to evangelize; and (3) sending disciples to engage in practical actions, which in turn help with a better understanding of the Gospel field. Challenges encountered in evangelism could be used as research material, and the findings from research could be utilized to address the issues in the field. In this way, the interaction between research, training, and sending has become a crucial aspect of implementing the “Threefold Vision”.[71] In fact, as early as 1990, when Chao was drafting the 10-year plan for Christ’s College, the concept of research, training and sending already existed. When he explained how the Vision became the mission of the school, he pointed out the essence of the Vision: “(The Vision has) evangelizing the Chinese People as our goal, training workers as the means, and research and planning as aids.” As to the achievement of the Vision, Chao summarized as follows: “The vision is to be realized through prayer, commitment, research, planning, communication, hard labor, and teamwork. ”[72]

In a nutshell, for Jonathan Chao, the implementation of the “Threefold Vision” is to be achieved through research, training, and sending, and the interaction between these three elements, which undoubtedly entails commitment to the vision and good teamwork.

Ying Shan teaches Systematic Theology at seminary and serves as Consultant Pastor at church. She was equipped with Master of Divinity and Master of Theology degrees in Hong Kong, and received a Doctor of Theology in a North American seminary. Ying Shan received the vision and burden to serve the Chinese in her college years. She was deeply moved by the “Three Vision” during the first stage of seminary training. She is deeply convicted that Christ’s love and salvation are able to bring renewal and transformation for individuals, churches, and nations. ↩︎

Wang Siyue, ed. “The Chronological Biography of Jonathan Chao 1938-2004,” The First Jonathan Chao Academic Symposium 2014. (Taipei: Jonathan Chao Archives Center, 2014), 85. ↩︎

Jonathan Chao, “The Development of Vision Outline,” unpublished lecture outline, 50-1. ↩︎

The seven callings are “Evangelism,” "Evangelism to the Far East,” “Theological Education in China,” “Chinese and Mainland Church Research,” “Evangelism in the Mainland,” “Theological Education in the Evangelization of China,” and “Christianization of Culture.” See “The Development of the Threefold Vision,” China and the Church, 83 (May-June 1991). ↩︎

In Chao's article “The Development of the Threefold Vision,” he referred to the background of his personal vision using the term “the influence of patriotism.” However, in his lecture outline titled "The Development of the Vision Outline,” he expressed this concept in English as the “sense of Chinese need”. ↩︎

There are as many as six colleges/seminaries associated with Dr. Chao, including: China Graduate School of Theology (Founder and Dean 1975-1980); China Evangelical Seminary (Academic Dean, 1986); Chinese Mission Seminary (Founder and President, 1987-2000); Tao-sheng Theological Seminary (President, 1988-1989); Christ’s College Taipei (Dean, 1989-1992); and China Theological Seminary (Founder). See “The Chronological Biography of Jonathan Chao 1938-2004”. ↩︎

Jonathan Chao, “The Development of the Threefold Vision,” Help Me Forward (Taipei: CMI Publishing, 1998), 16. ↩︎

The earliest research centers established by Chao include: the Christianity Research Center in Philadelphia (1969); the Chinese Church Research Center in Hong Kong (1978), originally a department of the China Graduate School of Theology (CGST) before becoming independent in 1980 and renamed China Ministries International (CMI) in Hong Kong in 1994. In 1986, he established the Christianity and Chinese Culture Research Center in Taiwan, which was renamed China Ministries International (CMI) a year later. In 1998, he founded the CMI Theological Institute in Taipei, aiming to train teaching and research scholars in Christian and Chinese studies. (See “The Chronological Biography of Jonathan Chao 1938-2004”). ↩︎

When Chao passed away, the house church leaders were shocked and deeply grieved for his passing. Pastor Chao had walked closely side by side with the house churches, showing great concern and providing guidance to the house church leaders when they encountered various problems. When the news of Chao’s passing broke, the house churches lamented: “Who shall we go for help in the future?” (See Spiritual Refining: Pastor Jonathan Chao Memorial Special Issue, 21.) ↩︎

Chao has written many articles directly related to Evangelization of China, including: “My Land and My People: A Vision of Evangelization of China”; “The Vision of Chinese Church Research Center”; “The Challenge of a Billion Souls”; and “Chinese Mission Seminary and Evangelization of China”. All of the articles were included in the China and the Church Journal, and can also be found in Help Me Forward. In addition, research articles on “The Evangelization of China” include B, K. Mak , “An Interpretation and Analysis on the Threefold vision of Jonathan Chao (Part I): Evangelization of China,” CMS Jounral, 5 (2005), 25-50. ↩︎

Jonathan Chao, “The Development Process of the Threefold Vision,” Help Me Forward, 10. Mak also pointed out that Chao often shared the gospel to friends and strangers. He loved to talk to people; and for those who didn't believe in Jesus, talking means talking about the gospel. See Mak, “An Interpretation and Analysis on the Threefold vision of Jonathan Chao (Part I): Evangelization of China,” 27. ↩︎

Jonathan Chao, “The Development Process of Threefold Vision,” China and the Church, 83 (May-June 1991), 13. ↩︎

Jonathan Chao, “The Challenge of a Billion Souls,” Help Me Forward, 57. ↩︎

Jonathan Chao, “Our Land and Our People—The Vision of Evangelization of China,” Help Me Forward, 47-48; “The Challenge of a Billion Souls,” Help Me Forward, 58-60. ↩︎

Jonathan Chao, “The Challenge of a Billion Souls,” Help Me Forward, 63. ↩︎

Jonathan Chao, “My Land and My People—The Vision of Evangelization of China,” Help Me Forward, 48-50; “The Challenge of a Billion Souls”, Help Me Forward, 60-62. ↩︎

Jonathan Chao, “My Land and My People—The Vision of Evangelization of China,” Help Me Forward, 46. ↩︎

Jonathan Chao, “The Vision of Chinese Church Research Center,” Help Me Forward, 51. ↩︎

Jonathan Chao, “The Challenge of a Billion Souls,” Help Me Forward, 65. ↩︎

Jonathan Chao, “The Foundation of Ministry with the Threefold Vision,” Help Me Forward, 31. ↩︎

Chen Yu, “Pastor Jonathan Chao's Statement,” Passing the Baton, 280. ↩︎

Jonathan Chao, “The Vision of Chinese Church Research Center,” Help Me Forward, 52-54. ↩︎

Jonathan Chao, “From Vision to Classroom,” "Rethinking Theological Education through the lens of Mission,” “China Ministries International’s Guidelines for Theological Education,” Help Me Forward, 81-83, 86-88, 90-91. ↩︎

Jonathan Chao, “Chinese Mission Seminary and the Evangelization of China,” Help Me Forward, 68. ↩︎

Jonathan Chao, ed., “Preface,” The Training Manual for Church Workers (Pasadena: China Ministries International, 1995), II. ↩︎

Jonathan Chao, “Chinese Mission Seminary and the Evangelization of China,” Help Me Forward, 68-69. ↩︎

Jonathan Chao, “Reflections on Migration: The Prospect of Chinese Mission Seminary,” China and the Church, 39 (February 1985), 2; see also B. K. Mak, “An Interpretation and Analysis on the Threefold Vision of Jonathan Chao (Part II): Kingdomization of the Chinese Church,” CMS Journal, 6 (2006), 168-169. ↩︎

See also Jonathan Chao, “The Vision of the Center for Chinese Church Studies: The Evangelization of China and the Christianization of Chinese Culture,” China and the Church, 44 (July 1985), 2-3. ↩︎

Jonathan Chao, “The Development of the Threefold Vision”, Help Me Forward, 16-17. ↩︎

Jonathan Chao, “China's Future Spiritual Project,” Faith and Life, 143 (July-September 1985), 155. ↩︎

Mak, “The Kingdomization of the Chinese Church,” 165. ↩︎

This is most likely a reference to Chao's interpretation of Romans 5-8. ↩︎

Jonathan Chao, “Chinese Mission Seminary and the Evangelization of China,” Help Me Forward, 70. ↩︎

Jonathan Chao, “The Development of Vision Outline,” 50-1. ↩︎

Jonathan Chao, The Theology of Salvation (Taipei: Olive, 2016), 62-63. ↩︎

Jonathan Chao, The Theology of Salvation, 70-71. ↩︎

Jonathan Chao, The Theology of Salvation, 242. ↩︎

Jonathan Chao, “Chinese Mission Seminary and the Evangelization of China,” Help Me Forward, 70. ↩︎

Jonathan Chao, The Theology of Salvation, 223-224. Citing the issue of the millennium as an example, personal people would have their own conviction according to different Biblical interpretations. However, as long as they believe in the Lord's return, they may hold their belief about the millennium according to their own understanding, and should tolerate others’ views based on their respective interpretations. ↩︎

X. R. Lu, “Be a Disciple of Heaven,” China and the Church, 47 (October 1985), 11; Quoted from B.K. Mak, “An Interpretation and Analysis on the Threefold vision of Jonathan Chao (Part II): The Kingdomization of the Chinese Church,” 170. ↩︎

Jonathan Chao, “The Development of Vision Outline”, 50-5. ↩︎

Jonathan Chao, “Walking through the Years of Thanksgiving”, Help Me Forward, 109. ↩︎

Jonathan Chao, “China Mission Seminary and the Evangelization of China,” Help Me Forward, 70. ↩︎

Jonathan Chao, “The Relationship between the Future of Chinese Culture and the Gospel,” Help Me Forward, 191. ↩︎

Jonathan Chao, “The Development of the Threefold Vision,” Help Me Forward, 9. ↩︎

See “The Development of Vision Outline,” 50–4. ↩︎

Jonathan Chao, “The Development of the Threefold Vision,” Help Me Forward, 9. ↩︎

Jonathan Chao, “Reflections on the 10th Anniversary of the Chinese Church Research Center,” Help Me Forward, 101. ↩︎

Jonathan Chao, “The Development of the Threefold Vision,” Help Me Forward, 18. ↩︎

Ibid., 13. ↩︎

Ibid. ↩︎

Wang Siyue, ed., “The Chronological Biography of Jonathan Chao 1938-2004,” 83. ↩︎

See Jonathan Chao, “Chinese Humanism and the Nature of Christianity,” The Awakening of Superman (December 1970), 95-122; reprinted in Helping Me Forward, 142-160. ↩︎

See Jonathan Chao, “The Relationship between the Gospel and Culture from the Perspective of Chinese History,” Campus Magazine (April 1986), 4-9; Jonathan Chao, “The Gospel and the Renewal of Chinese Culture,” Chinese Church Today, 109 (November 1987), 11-13; reprinted in Help Me Forward, 165-184; and “The Future of Chinese Culture and Its Relationship with the Gospel” and “Reflecting on the Relationship between the Gospel and Culture from the History of China Missions,” see Jonathan Chao, Help Me Forward, 185-204. ↩︎

Jonathan Chao, “The Gospel and the Renewal of Chinese Culture,” Help Me Forward, 184. ↩︎

Jonathan Chao, “The Relationship between the Future of Chinese Culture and the Gospel,” Help Me Forward, 191. ↩︎

Jonathan Chao, “Reflecting on the Relationship between the Gospel and Culture from the History of China Missions,” Help Me Forward, 199, 203. ↩︎

Jonathan Chao, “Thanksgiving as Offering to God,” Help Me Forward, 41. ↩︎

Ibid., 42. ↩︎

Jonathan Chao, “The Development of the Threefold Vision,” Help Me Forward, 15. ↩︎

In August 1987, a committee meeting of the Three-Self Churches and China Christian Council was held in Chengdu. Mr. Han Wenzao, vice president of the Council in charge of foreign affairs, spoke at the meeting, accusing Jonathan Chao of “overthrowing the socialist New China led by the Communist Party”. The speech was later published in the Tian Feng (Heavenly Wind) Magazine with a scathing commentary. The author employed strong and highly aggressive language. Such intensity was rarely seen. Chao believed that this was a deliberate attempt to create an “anti-communist” image. However, he reiterated that he had nothing to do with any political regime or politics. And as a Chinese Christian, he only expressed his patriotism by preaching the gospel. “A Discussion with Pastor Jonathan Chao on the Accusations against Him in Tian Feng Magazine (Heavenly Wind),” China and the Church, 64 (March-April 1988), 5-7. ↩︎

Jonathan Chao, “The Development of the Threefold Vision,” Help Me Forward, 12. ↩︎

Jonathan Chao, “Through the Years of Gratitude,” Help Me Forward, 59; Jonathan Chao, “Christ’s College and the Gospel Vision,” Christ’s College News 51 (November 1989), see Help Me Forward, 114. ↩︎

Jonathan Chao, “Reflection on the Relationship between the Gospel and Culture from the History of China Missions,” Help Me Forward, 201-203. ↩︎

Jonathan Chao, “Reflection on the Relationship between the Gospel and Culture from the History of China Missions,” Help Me Forward, 204. ↩︎

Jonathan Chao, “The Foundation of Ministry with the Threefold Vision,” Help Me Forward, 23. ↩︎

Jonathan Chao, “The Direction of Christ's College,” Christ's College News 53 (February 1990), reprinted in Help Me Forward, 118. ↩︎

College News articles include “Christ's College and the Gospel Vision,” Christ's College News 51 (November 1989); “The Direction of Christ's College,” Christ's College News 53 (February 1990); “Holistic Education--The Philosophy of Christian Liberal Education,” Christ’s College News 55 (May 1990); “Pursuing Eternal Love and Bearing the Fruits of Benevolence and Righteousness,” 65 (May 1992), reprinted in Help Me Forward, 112-130. ↩︎

Jonathan Chao, “Relaunch in Ministry", reprinted in Help Me Forward, 133-134. ↩︎

Jonathan Chao, “The Foundation of Ministry with the Threefold Vision,” Help Me Move Forward, 27. ↩︎

Ibid, 29. ↩︎

Jonathan Chao, “The Development of Vision Outline,” 50-8. ↩︎